Dennis Cooper, Jahrgang 1953, hat den Ruf eines Kultautors, kam aber nie im Mainstream an. Das mag daran liegen, dass ihm früh der Stempel eines ‘enfant terribles’ aufgedrückt wurde, der mit expliziten Darstellungen von Sex und Gewalt provozieren wolle. Zurzeit befindet er sich in einer Hochphase: Ende vergangenen Jahres erschien sein zehnter Roman I Wished. Zur gleichen Zeit verlegte der Luftschacht Verlag erstmals seinen 2004 veröffentlichten Roman Die Schlampen in deutscher Sprache (Orig. The Sluts). Aktuell befindet er sich in den Vorbereitungen zu seinem dritten Film und pflegt beinah täglich seinen Blog. Zwischenzeitlich fand er noch die Zeit für ein Interview mit mir (Read English version here).

Dennis Cooper, Jahrgang 1953, hat den Ruf eines Kultautors, kam aber nie im Mainstream an. Das mag daran liegen, dass ihm früh der Stempel eines ‘enfant terribles’ aufgedrückt wurde, der mit expliziten Darstellungen von Sex und Gewalt provozieren wolle. Zurzeit befindet er sich in einer Hochphase: Ende vergangenen Jahres erschien sein zehnter Roman I Wished. Zur gleichen Zeit verlegte der Luftschacht Verlag erstmals seinen 2004 veröffentlichten Roman Die Schlampen in deutscher Sprache (Orig. The Sluts). Aktuell befindet er sich in den Vorbereitungen zu seinem dritten Film und pflegt beinah täglich seinen Blog. Zwischenzeitlich fand er noch die Zeit für ein Interview mit mir (Read English version here).

Ich habe kürzlich de Sades Die 120 Tage von Sodom gelesen – auch, weil du de Sade als Einfluss auf dich als Schriftsteller anführst. Ich dachte, ich hätte alles gesehen, was auf eine Seite geschrieben werden könnte – wie habe ich mich geirrt! Da es sich um ein skandalöses Buch von einem skandalösen Schriftsteller handelt, ist der Reiz an und für sich klar – verbotene Früchte schmecken bekanntlich am besten. Fangen wir also gleich hier an: Wann und warum hast du angefangen, de Sade zu lesen, und wie hat die Lektüre deine Herangehensweise an Literatur verändert?

Dennis Cooper: Ich habe de Sade gefunden und gelesen, als ich 15 war. Die 120 Tage von Sodom standen auf dem Bücherregal des Sohnes einiger Freunde meiner Eltern, die wir besuchten. Ich hatte von Sade gehört, also zog ich es heraus und fing an, darin zu lesen. Als mir klar wurde, wie extrem es war, stahl ich das Buch und versteckte es in meinem Koffer und las es heimlich. Es war eine riesige Offenbarung, weil ich seit meiner Kindheit von intensiven Fantasien über Sex und Gewalt heimgesucht wurde, und ich war sehr verwirrt von ihnen und was sie über mich sagen könnten. Zu sehen, dass es legitim ist, über derart extreme Themen zu schreiben und dass sie veröffentlicht werden und sogar von klugen Leuten wie Simone de Beauvoir und Maurice Blanchot, deren Essays über den Roman in der Grove Press-Ausgabe enthalten waren, geschätzt werden, war ziemlich augenöffnend für mich. Ich schrieb bereits seit meiner Kindheit und mir wurde klar, dass ich versuchen könnte, über diesen verborgenen Aspekt von mir selbst zu schreiben und so begann ich praktisch sofort damit. Es ist schwer zu übertreiben, was für ein einschneidendes Erlebnis das für mich als Künstler und als Mensch im Allgemeinen war.

Das Buch von dir, das meiner Meinung nach am meisten an de Sage erinnert, ist The Marbled Swarm. Nicht nur in Bezug auf die Umgebung (ein abgelegenes Schloss), sondern auch auf die Sprache: Die Sätze sind tendenziell länger und komplexer als in anderen Romanen. Ich muss gestehen, dass es mir schwer gefallen ist, The Marbled Swarm zu lesen und ich habe das Gefühl, dass ich den Text nicht ganz durchdrungen habe. Da ich gerade Die 120 Tage von Sodom gelesen habe und mir beim Lesen The Marbled Swarm in den Sinn kam, interessiert mich, ob du mir zustimmen würdest, dass es der Roman ist, der am deutlichsten von de Sade beeinflusst ist oder ob ich völlig daneben liege? Mich würde auch interessieren, welchen Effekt du mit The Marbled Swarm erzielen wolltest und ob es etwas damit zu tun hat, dass du im Anschluss ein Jahrzehnt keine Romane (außer den GIF-Romanen) veröffentlicht hast?

Dennis Cooper: Ich habe nicht an Sade gedacht oder versucht, mich in The Marbled Swarm bewusst auf ihn zu beziehen, aber ich verstehe vollkommen, warum es wie mein „de Sade“-Roman wirkt, besonders angesichts der sehr dichten und verschnörkelten Prosa, mit der ich gearbeitet habe. Was mein Ziel betrifft, so wollte ich einen Roman schreiben, bei dem der Roman selbst das Wichtigste war und das, was darin vor sich ging, zweitrangig gegenüber dem war, was die Struktur und das Schreiben des Romans bewirkten. Ich wollte einen Roman schreiben, in dem die Sprache voller Geheimnisse und versteckter Passagen ist, bis sie so dreidimensional wie möglich erscheint. Das war ein großes Ziel von mir, seit ich mich in jungen Jahren zum ersten Mal entschied, ein ernsthafter Schriftsteller zu werden und ich hatte schon früher versucht, einen Roman wie diesen zu schreiben, aber ich brauchte viele Jahre, um die Fähigkeiten und Fertigkeiten zu erwerben, um es tatsächlich hinzubekommen. Es ist mein Favorit unter meinen Romanen. Ich weiß, dass er sehr schwierig und anspruchsvoll ist, aber ich denke, das ist es, was ich daran mag. Ich liebe Literatur und Filme und Kunst und Musik, die verwirren, aber dennoch sehr klar und genau realisiert sind. Ich habe das Gefühl, dass mir das mit The Marbled Swarm gelungen ist.

Der Roman hatte nichts damit zu tun, dass ich zehn Jahre brauchte, um meinen nächsten Roman I Wished fertigzustellen. Das lag hauptsächlich daran, dass ich mich sehr dafür interessierte, Filme mit Zac Farley zu machen und zu versuchen, Romane zu schreiben, die aus animierten Gifs bestehen. Ich nehme an, ich wollte auch eine Pause vom Schreiben von Romanen einlegen, da ich mich so lange darauf konzentriert hatte, im Grunde ununterbrochen, einen nach dem anderen geschrieben habe. Ich habe immer das Bedürfnis, meine Herangehensweise an einen neuen Roman neu zu erfinden. Zwischen dieser Suche und der Beschäftigung mit den Filmen und Gif-Romanen brauchte ich einfach länger als gewöhnlich, um einen neuen Weg zu finden, einen Roman zu schreiben, der mich in dieser Hinsicht angeregt hat.

Da dir Struktur so wichtig ist und ich als Leser manchmal das Gefühl habe, dass die Struktur eines Romans selbst der Schlüssel zu allem anderen darin ist, frage ich mich, wie aufwendig der Planungsprozess ist – arbeitest du eine Outline aus, die du beim Schreiben abarbeitest oder ist es ein organischerer Prozess?

Dennis Cooper: Es kommt auf den Roman an. Für die George-Miles-Zyklus-Bücher habe ich viele Jahre damit verbracht, die Struktur des Zyklus und die Strukturen der einzelnen Romane innerhalb der Gesamtstruktur des Zyklus zu entwerfen. The Marbled Swarm war ein weiterer Roman, der viel Experimentieren und Vorausplanen erforderte. Aber mit I Wished habe ich mich beispielsweise bewusst gegen meine übliche Tendenz entschieden, die Strukturen aufwendig vorab zu planen. Ich wollte, dass der Text so emotional wie möglich erzeugt wird. Dieser Roman wurde sehr intuitiv mit einer „alles geht“-Einstellung geschrieben und dann ging ich später zurück zu dem Material, das ich geschrieben hatte, und durchsuchte es nach Verbindungen und strukturierte während des Lektorats. Die Schlampen hingegen habe ich im Laufe von zehn Jahren geschrieben, wobei ich ständig verschiedene Wege ausprobiert habe, den Text aufzubauen. Als ich in den 90er Jahren anfing, diesen Roman zu schreiben, gab es noch kein richtiges Internet, also kam das Internet-Setting, das für den Roman von entscheidender Bedeutung ist, erst später hinzu. Dieser Roman hat also eine komplizierte Struktur, wie die meisten meiner Romane, aber er entstand durch einen Prozess des ständigen Aufbauens und Abreißens und Wiederaufbauens usw.

Eine der wenigen Auszeichnungen, die du erhalten hast, ist der Prix Sade, der dir 2007 für Die Schlampen verliehen wurde (das muss eine Art „Kreisschluss“-Moment gewesen sein, wenn man bedenkt, was de Sade für dich bedeutet). Dieser Roman ist gerade zum ersten Mal auf Deutsch erschienen und eine Rezensentin hat dich als das „Enfant terrible der gay fiction“ bezeichnet. Das wirft natürlich die Frage auf, was schwule Literatur eigentlich ist und warum wir diese Bezeichnung überhaupt brauchen. Aber viel interessanter ist die Frage, ob diese Betrachtungsweise deiner Kunst dazu geführt hat, God, Jr. zu schreiben, einen Roman ohne schwule Charaktere, der dennoch in der Art und Weise, wie er Verlust und die Unmöglichkeit, einen anderen wirklich zu kennen, erforscht, ein typischer Dennis-Cooper-Roman ist. Das Buch verbindet sich mit so vielen Dingen deiner anderen Texte, nur in einem heteronormativen Kontext. In God jr. errichtet der Vater, der um seinen Sohn trauert, ein Denkmal für ihn, genauso wie du – so könnte man argumentieren – beispielsweise ein literarisches Denkmal für deinen Freund George Miles errichtet hast. Eigentlich schreibst du über ziemlich universelle Dinge – war God, Jr. ein Versuch, aus der Schublade des „schwulen Schriftstellers“ auszubrechen, und wie siehst du das heute rückblickend?

Dennis Cooper: Ich weiß, dass die Leute eine vorgefertigte Vorstellung davon haben, was ein „Dennis Cooper“-Roman ist. Seit ich angefangen habe, wurde ich so ziemlich in die Kategorie „böser Junge“, „enfant terrible“ eingeordnet. Aber ich sehe mich natürlich nicht als Autor, der diese Rolle spielt oder der einen bestimmten Kontext hat, in dem ich arbeite. Ich bin kein Genreschreiber, ich bin ein Experimentator. Also fühle ich mich von dieser Erwartung nicht eingeschränkt. Ich denke einfach nicht darüber nach oder befasse mich mit dem, was die Leute von mir erwarten.

Dennis Cooper: Ich weiß, dass die Leute eine vorgefertigte Vorstellung davon haben, was ein „Dennis Cooper“-Roman ist. Seit ich angefangen habe, wurde ich so ziemlich in die Kategorie „böser Junge“, „enfant terrible“ eingeordnet. Aber ich sehe mich natürlich nicht als Autor, der diese Rolle spielt oder der einen bestimmten Kontext hat, in dem ich arbeite. Ich bin kein Genreschreiber, ich bin ein Experimentator. Also fühle ich mich von dieser Erwartung nicht eingeschränkt. Ich denke einfach nicht darüber nach oder befasse mich mit dem, was die Leute von mir erwarten.

Vor God, jr. hatte ich mich schon lange dafür interessiert, was für einen Roman ich schreiben würde, wenn ich Sex und queere Charaktere und sexuelles Verlangen als Antrieb ausschließe. Ich bin auch ein großer Fan von Videospielen. Ich habe viel über Räumlichkeit und erzählerische Möglichkeiten aus der Art und Weise gelernt, wie Videospiele aufgebaut sind und aus der getriebenen, aber frei schwebenden Erfahrung, die sie den Spielern bieten. Also habe ich mich bei God Jr. entschieden, diesen Bereich bewusst zu erkunden und das hat mich so begeistert, dass ich das triebhafte Material, mit dem ich normalerweise arbeite, nicht für nötig hielt. In diese Richtung hatte ich mich bereits mit dem Vorgängerroman Mein loser Faden bewegt, wo die Konzentration auf Sex/Gewalt auf explizite Weise bereits verringert wurde. Ich bin immer noch ziemlich stolz auf God Jr. Ich denke, der letzte Abschnitt dieses Romans ist wahrscheinlich das Beste, was ich je geschrieben habe. Es ist interessant für mich, dass damals Leute, die an meiner Arbeit beteiligt waren, wie mein Agent und Verleger und so weiter, mir lange gesagt hatten, dass der einzige Grund, warum meine Arbeit nicht wirklich erfolgreich und von den Kritikern gelobt wurde, meine schwierigen Themen sein. Sie glaubten, dass God, Jr. mein Durchbruch sein würde, obwohl das natürlich nicht der Fall war. Ich war damals schon zu sehr durch den Ruf meiner vorherigen Arbeit stigmatisiert, also hat God, Jr. nur die Leute verwirrt, die dachten, sie würden mich verstehen.

Um auf Die Schlampen zurückzukommen: Als der Roman ursprünglich veröffentlicht wurde, steckte Facebook noch in den Kinderschuhen und Fake News als Begriff war noch nicht einmal am Horizont. Man kann also behaupten, der Roman ist sehr gut gealtert. Die Schlampen besteht aus Online-Rezensionen und Chats auf schwulen Message Boards und Dating-Sites. Wir wissen nicht, wer oder wie viele sprechen. Es gibt keine „Wahrheit“, nur Gerüchte und Fantasien, die irgendwie außer Kontrolle geraten. Da Die Schlampen älter als die sozialen Medien ist und das, was sie meiner Meinung nach dem öffentlichen Diskurs angetan haben, in dieser Erzählung praktisch vorweggenommen wurde, frage ich mich, inwieweit (wenn überhaupt) sich seitdem deine Einstellung zum Internet geändert hat und ob sich irgendetwas an Die Schlampen veraltet anfühlt, da die Erzählung in einem Medium spielt, das sich oberflächlich betrachtet ziemlich verändert hat?

Um auf Die Schlampen zurückzukommen: Als der Roman ursprünglich veröffentlicht wurde, steckte Facebook noch in den Kinderschuhen und Fake News als Begriff war noch nicht einmal am Horizont. Man kann also behaupten, der Roman ist sehr gut gealtert. Die Schlampen besteht aus Online-Rezensionen und Chats auf schwulen Message Boards und Dating-Sites. Wir wissen nicht, wer oder wie viele sprechen. Es gibt keine „Wahrheit“, nur Gerüchte und Fantasien, die irgendwie außer Kontrolle geraten. Da Die Schlampen älter als die sozialen Medien ist und das, was sie meiner Meinung nach dem öffentlichen Diskurs angetan haben, in dieser Erzählung praktisch vorweggenommen wurde, frage ich mich, inwieweit (wenn überhaupt) sich seitdem deine Einstellung zum Internet geändert hat und ob sich irgendetwas an Die Schlampen veraltet anfühlt, da die Erzählung in einem Medium spielt, das sich oberflächlich betrachtet ziemlich verändert hat?

Dennis Cooper: Die Prämisse und Struktur von Die Schlampen basierten auf einer Website, die zu der Zeit existierte, auf der Escorts ihre Dienste bewarben und Kunden ihre Bewertungen und Diskurse über die Escorts veröffentlichten. Da wurde ziemlich viel fantasiert und gelogen und fabriziert, nicht in dem riesigen Ausmaß wie in Die Schlampen, aber ich war fasziniert von der Möglichkeit, dass man dort ganz einfach einen massiven Streich a la Die Schlampen hätte treiben können. Ich habe gewissermaßen die Website aus dem Internet gerissen und sie auf das unflexible Papier eines Romans verpflanzt und es weiter zugespitzt. Ich weiß nicht, ob du meinen Blog liest, aber einmal im Monat sammle ich Escort-Anzeigen und Kundenkommentare/Bewertungen von verschiedenen bestehenden Escort-Sites und veröffentliche die interessantesten mit ein wenig Bearbeitung und Verschleierung meinerseits, und das ist noch nichts so Krasses wie das, was in Die Schlampen passiert, auch wenn es in einigen Fällen nah dran ist. In diesem Sinne scheint Die Schlampen also irgendwie vorausschauend zu sein.

Ich glaube also nicht, dass Die Schlampen veraltet ist – oder noch nicht, obwohl das zweifellos der Fall sein wird – hauptsächlich, weil die Übertragung der Internet-Interaktivität auf die unbewegliche gedruckte Seite einen Einfriereffekt hat. Ich denke, dass Die Schlampen jetzt eine gewisse Kuriosität haben könnte, wenn man bedenkt, dass das derzeitige Internet von wilden Verschwörungstheorien, Hacking-Angriffe und Click-Bait usw. voll ist, also hat es vielleicht in diesem Sinne eine Vintage-Atmosphäre, eine Art “Vinyl vs. MP3”-Wirkung oder so.

Was den Blog betrifft bin ich erstaunt, dass du es schaffst, fast jeden Tag etwas zu posten während du gleichzeitig Romane schreibst und Filme machst. Hast du so etwas wie einen Arbeitszeitplan?

Dennis Cooper: Abgesehen von dem p.s.-Abschnitt des Blogs, dem ich mich jeden Morgen widme, nein. Ich verbringe den größten Teil meiner Freizeit damit, die Blog-Posts zu schreiben. Wenn ich mit einem anderen Projekt oder lebensbezogenen Dingen beschäftigt bin, finde ich jeden Tag ein oder zwei Stunden, um einen Beitrag zu erstellen. Wenn ich zwischen Projekten stecke, wie aktuell, da ich darauf warte, dass die Finanzierung für meinen nächsten Film mit Zac Farleys zustande kommt und ich noch an einigen literarischen Ideen herumfummele, lenke ich einfach den Großteil meiner kreativen Energie in den Blog. Ich habe immer jede Menge Neugier und Energie, also kann ich ziemlich produktiv sein. Im Moment habe ich Blog-Beiträge für etwa drei Wochen vorbereitet.

Der neue Roman I Wished kehrt zur Muse des George-Miles-Zyklus zurück. Der Roman handelt, würde ich sagen, ebenso sehr von deinem Freund George wie von dir als Künstler. Mein Lieblingsabschnitt ist das Kapitel „Der Krater“. Hier schreibst du über den Roden-Krater und James Turrell, der ihn zu einer Kunstinstallation formt. Da gibt es diesen lustigen Satz über Turrell, von dem du dir vorstellst, dass er denkt: „Ich liebe und verachte dieses alte Ding so sehr, dass ich mein Leben darauf verwenden werde, daraus mein größtes Kunstwerk zu formen“. Dieser Satz erinnert mich an Joan Didions berühmtes Zitat „Writers are always selling someone out“. Da du es in I Wished explizit machst, hattest du jemals Hemmungen, George Miles zu Kunst zu „formen“?

Dennis Cooper: Als ich den Zyklus entwickelte, lebte George noch. Und ich habe viele Gespräche mit ihm darüber geführt, was ich mit diesen Romanen vorhabe und wie ich beabsichtigte, ihn darzustellen beziehungsweise zu verfremden. Er war völlig einverstanden mit dem, was ich plante und war sehr ermutigend. Er war begeistert von der Idee, ein formbares, fiktives Gefäß zu sein. Wie ich in I Wished geschrieben habe, fühlte er sich aufgrund seiner psychischen Störung und der Wirkung, die seine Medikamente auf ihn hatten, als Person sehr verloren und er interessierte sich für die Idee, sich in einen überzeugenden literarischen Charakter zu kristallisieren. Also hatte ich keine Bedenken, ihn als Art Repräsentationsfigur im Zyklus zu verwenden. Wie du sicherlich weißt, hat sich George umgebracht, bevor der erste Roman des Zyklus, Closer, veröffentlicht wurde, was ich erst erfuhr, als ich dabei war, den fünften und letzten Roman Period zu schreiben. Diese sehr schockierende Nachricht verkomplizierte das ganze Projekt für mich extrem, da ich dachte, er würde irgendwo die Bücher lesen. Deshalb ist Period ein so verwirrter/verwirrender Illusionsroman geworden.

I Wished wurde geboren, um zu versuchen, George gerecht zu werden, indem ich ihn so darstellte, wie er – soweit ich ihn verstehen konnte – wirklich als Person war. Ich denke, der Roman handelt viel mehr von mir und dem, was George mit meiner Vorstellungskraft macht, als von ihm. Ich fühle mich sehr widersprüchlich darüber, George in Kunst zu verwandeln und ich denke oder hoffe zumindest, dass der Roman dies an jedem Punkt deutlich macht.

I Wished ist auch eine Art Ruf, dass sich jemand, der ihn kannte, mit dir in Verbindung setzt. Er ist lange vor dem Internet gestorben und du schreibst, du konntest niemanden ausfindig machen, der ihn kannte. Hat die Veröffentlichung von I Wished diesbezüglich etwas gebracht?

Dennis Cooper: Kurz nach der Veröffentlichung von I Wished kontaktierte mich eine Frau, um mir zu sagen, dass sie den Roman gelesen und ihre Möglichkeiten als Angestellte einer Zeitung genutzt hatte, um Georges Bruder aufzuspüren. Das war erstaunlich für mich, weil ich viele Jahre immer wieder versucht habe, seinen Bruder ausfindig zu machen. Er ist Arzt und sie konnte die Telefonnummer seiner Praxis auftreiben, aber keine E-Mail-Adresse. Seitdem überlege ich, ob ich ihn anrufen soll. Ich bis zwiegespalten, da ich erstens nicht weiß, ob er von meinen Büchern für George weiß und was er darüber denken würde, und zweitens, ob er über seinen Bruder sprechen möchte, da sein Selbstmord für seine Familie sehr dramatisch und traumatisch war. Ich habe also eine Möglichkeit, Georges Bruder telefonisch zu kontaktieren, aber ich weiß nicht, ob ich den Mut habe, ihn so direkt anzusprechen.

Abgesehen davon, nein, niemand sonst, der George kannte, hat sich bei mir gemeldet, zumindest noch nicht.

Mit I Wished erweiterst du einmal mehr das allgemeine Verständnis von dem, was ein Roman ist, da er Märchen, Memoiren, Essay und vieles mehr in einem vereint. Der Erzählung gelingt das Kunststück, sowohl strukturell herausfordernd als auch ziemlich einfach zu lesen und nachvollziehbar zu sein. Der Roman könnte auch als Endpunkt und als neue Richtung für dich als Autor gelesen werden. Wie groß ist dein Interesse am Roman als Kunstform, nachdem du dich in den letzten Jahren dem Film zugewandt hast?

Dennis Cooper: Ich hatte einen langjährigen Plan, 10 Romane zu schreiben – die 5-Zyklus-Romane und 5 Post-Zyklus-Romane – und dann damit aufzuhören. Ich denke, ich mochte am meisten die Symmetrie von 5/5, und ich dachte, 10 Romane sind viel von einem Autor. Also sollte I Wished der letzte sein, und als ich mich für das Filmemachen und die Gif-Fiction zu interessieren begann und I Wished für etwa fünf Jahre beiseite legte, dachte ich, ich würde zurückgehen und es fertigstellen und dann ist Schluss. Aber als ich zum Roman zurückkam und ihn beendete, wieder in diesen Headspace zurückgekehrt war, war es so ein Vergnügen. Ich fühlte die gleiche Aufregung in Bezug auf die damit verbundenen Schwierigkeiten und Herausforderungen, die ich immer hatte, also entschied ich, es offen zu lassen, weitere Romane zu schreiben solange ich das Gefühl habe, dass dies die richtige Form für das ist, was ich tun möchte. Also, ja, ich scheine immer noch sehr an dem Roman als Form interessiert zu sein. Ich freue mich jetzt genauso darauf, Filme zu machen, aber ich sehe keinen Grund, warum ich nicht beides machen könnte. Wir werden sehen.

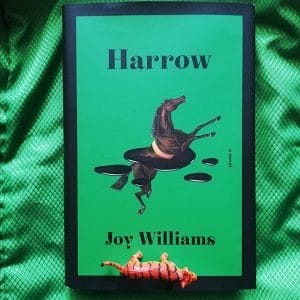

Kürzlich hast du im Apology-Podcast Joy Williams erwähnt. Ich bin ratlos, warum sie unbekannt ist! Ihr neuer Roman Harrow ist absolut unglaublich und sie ist wahrscheinlich meine Lieblings-Kurzgeschichtenautorin überhaupt. Letzte Frage: Welches ist dein Lieblingsbuch von Joy Williams und warum?

Dennis Cooper: Joy Williams ist wahrscheinlich meine liebste amerikanische Autorin, zumindest unter den lebenden Schriftstellern. Ich denke, John Ashbery ist insgesamt mein liebster amerikanischer Schriftsteller.

Es ist tatsächlich schwer, eines ihrer Bücher zu meinem Favoriten zu erklären. Auch ich habe Harrow wirklich geliebt und ich denke, es gehört zu ihren Besten. Vielleicht ist The Quick and the Dead mein Favorit von ihr. Das mag daran liegen, dass es das erste Buch von ihr ist, das ich gelesen habe, also ist das ist meine Wahl, wenn ich mich für eines entscheiden muss.

**

Dieser Blog ist frei von Werbung und Trackern. Wenn dir das und der Inhalt gefallen, kannst du mir hier gern einen Kaffee spendieren: Kaffee ausgeben.

**

„I’m an experimenter“: An Interview with Dennis Cooper

Dennis Cooper, born in 1953, has a reputation as a cult author but never made it into the mainstream. This may be due to the fact that early on he was labeled an ‚enfant terrible‘ whose texts feature plenty explicit depictions of sex and violence. His career is currently experiencing a sort of hayday: his new, tenth novel I Wished was published to widespread acclaim at the end of last year. At the same time, the Austrian Luftschacht Verlag published his 2004 novel The Sluts for the first time in German. A critical biography was written about him. He is currently preparing his third film and keeps his blog up to date pretty much every day. Yet he still found the time for an interview.

Dennis Cooper, born in 1953, has a reputation as a cult author but never made it into the mainstream. This may be due to the fact that early on he was labeled an ‚enfant terrible‘ whose texts feature plenty explicit depictions of sex and violence. His career is currently experiencing a sort of hayday: his new, tenth novel I Wished was published to widespread acclaim at the end of last year. At the same time, the Austrian Luftschacht Verlag published his 2004 novel The Sluts for the first time in German. A critical biography was written about him. He is currently preparing his third film and keeps his blog up to date pretty much every day. Yet he still found the time for an interview.

I recently read de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom – partly because you cite de Sade as an influence on you as a writer. I thought I had seen everything that could possibly be committed to a page, but boy was I wrong. Being a scandalous book from a scandalous writer, the appeal is clear – forbidden fruits taste best. So let’s start right here: When and why did you start reading de Sade and how did reading 120 Days of Sodom change your approach to literature?

Dennis Cooper: I found and read De Sade when I was 15. The 120 Days of Sodom was sitting on the bookshelf of the son of some friends of my parents whom we were visiting. I’d heard about Sade, so I pulled it out and started reading it. When I realised how extreme it was, I stole the book and hid it in my suitcase and read it secretly. It was a huge revelation because I’d been beset with intense fantasies about sex and violence since I was a kid, and I was very confused by them and what they might mean about me. Realising that such extreme subject matter was legitimate to write about and get published and even to be praised by brainy people like Simone de Beauvoir and Maurice Blanchot, whose essays on the novel were included in the Grove Press edition I was reading, was pretty massive to me. I was already writing and had been since childhood, and I realised I could try to write about that hidden aspect of myself, and so I started doing that pretty much straight away. It’s hard to overstate what a breakthrough that was for me as an artist and as a human being in general.

The most de Sadean book of yours is, in my opinion, The Marbled Swarm. Not only in terms of setting (a remote chateau), but also in terms of language. Your sentences tend to be longer and more complex than in other works of yours. I must admit that I had a hard time getting into The Marbled SwarmSince I’ve just read 120 Days of Sodom and The Marbled Swarm came to mind while reading it, I’m interested to know if you’d agree that this is the novel most clearly influenced by de Sade or if I’m completely off track here? And I’d also be interested to know what you actually set out to do when you wrote The Marbled Swarm and if it has anything to do with you not publishing novels (other than the GIF novels) for a decade?

Dennis Cooper: I wasn’t thinking about Sade or trying to reference him consciously in The Marbled Swarm, but I totally understand why it seems like my most Sadeian novel, especially given the very dense and ornate prose I was working with.

As for what I set out to do: I wanted to write a novel where the novel itself was the most important thing and what went on in it was secondary to what the novel’s structure and writing were doing. I wanted to write a novel where the writing was full of secrets and hidden passages to the point of being as three-dimensional as possible. Doing that had been a huge goal of mine since I first decided to be a serious writer when I was young, and I had tried to write a novel like that before but it took me many years to get the skills and chops to actually pull it off. It’s my favorite of my novels. I know it’s very difficult and demanding, but I suppose that’s what I like about it. I love fiction and films and art and music that’s very confusing to understand but very clearly and exactly rendered. I feel like I managed to do that with The Marbled Swarm.

The novel had nothing to do with my taking ten years to finish I Wished. That was mostly because I got very interested in making films with Zac Farley and in trying to write novels composed of animated gifs, and I concentrated on them. I suppose I also wanted to take a break from writing novels seeing as how I had been concentrating on writing novels basically nonstop, one after another, for such a long time. I always feel the need to reinvent my approach to the novel every time I start a new one, and between that search and being preoccupied with the films and gif novels, it just took me longer than usual to find a new way to write a novel that excited me enough.

Since structure is so important to you and as a reader I sometimes have the feeling that a novel’s structure itself is the key to unlock everything else in it, I wonder how elaborate the outlining process is – do you work out a plan you go by when actually writing it or is it a more organic process?

Dennis Cooper: It depends on the novel. For the George Miles Cycle books, I spent many years devising the cycle’s structure and the individual novels’ structures within the cycle’s overall structure. The Marbled Swarm was another novel that needed a lot of advance experimenting and pre-planning. But with I Wished, for instance, I deliberately went against my usual tendency to pre-plan novels’ structures in an elaborate way. I wanted it to be as emotionally generated as possible. That novel was written very intuitively with an ‘anything goes’ attitude, and then I went back to the material I’d written later and searched through it looking for connective tissue then structured it during the editing process.

With The Sluts, on the other hand, I wrote that novel over the course of ten years, constantly trying different ways of building it. When I first started writing it it in the 90s, there wasn’t a developed internet yet, so the internet setting, which is of key importance to the novel, came along later. So that novel has a complicated structure like most of my novels do, but it came about through a process of continually building things and tearing them down and rebuilding them, etc.

One of the few awards you have received is the Prix Sade, which was awarded to you for The Sluts in 2007 (that must have been a sort of ‘full circle’ moment given what de Sade means to you). That novel has just been published in German for the first time and one reviewer described you as the ‘enfant terrible of gay fiction’. This leaves the question of what gay fiction actually is and why we would need this nomer. But much more interesting to me is whether being looked though the ‚transgressive gay writer‘-lens led you to write God, Jr., a novel without gay characters yet is still very much a Dennis Cooper novel in the way that it explores loss as well as the impossibility of truly knowing someone else (at least that’s what I think is at the heart of many of your novels). The book connects to so many things of your other writing, just in a heteronormative setting. In God, jr., the father grieving the loss of his son is building a monument for him, just as you, one could argue, built a written monument for your friend George Miles, for example. Was God, Jr. an attempt to break out of the “gay writer” box and, looking back, how do you look at it today?

One of the few awards you have received is the Prix Sade, which was awarded to you for The Sluts in 2007 (that must have been a sort of ‘full circle’ moment given what de Sade means to you). That novel has just been published in German for the first time and one reviewer described you as the ‘enfant terrible of gay fiction’. This leaves the question of what gay fiction actually is and why we would need this nomer. But much more interesting to me is whether being looked though the ‚transgressive gay writer‘-lens led you to write God, Jr., a novel without gay characters yet is still very much a Dennis Cooper novel in the way that it explores loss as well as the impossibility of truly knowing someone else (at least that’s what I think is at the heart of many of your novels). The book connects to so many things of your other writing, just in a heteronormative setting. In God, jr., the father grieving the loss of his son is building a monument for him, just as you, one could argue, built a written monument for your friend George Miles, for example. Was God, Jr. an attempt to break out of the “gay writer” box and, looking back, how do you look at it today?

Dennis Cooper: I know that people have a pre-set idea of what a ‘Dennis Cooper’ novel is. I’ve been boxed into the ‘bad boy’, ‘enfant terrible’ category pretty much since I first started. But I, of course, don’t think myself as a writer who plays that part or who has some particular area in which I work. I’m not a genre writer, I’m an experimenter. So I feel disconnected from that expectation, and I just don’t think about it or consider what people are going to anticipate from me. I had been interested for a long time in discovering what kind of novel I would write if I excluded sex and queer characters and sexual desire as an impetus, and I’m a big fan of video games. I’ve learned a lot about spatiality and narrative possibilities from the way they’re built and from the driven but free-floating experience they offer players. So, with God, Jr., I just decided to explore that area in a deliberate way, and doing so excited me enough that I felt no need to include the fiery material I usually work with. I had already been moving in that direction with the prior novel My Loose Thread where the concentration on sex/violence in an explicit way was already diminished.

I’m still quite proud of God, Jr. I think the last section of that novel is probably the best thing I’ve ever written. It’s interesting to me that, at the time, people who had a stake in my work like my agent and publisher and so on, and who had a long told me that the only reason my work wasn’t really successful and acclaimed by the arbiters of the literary world was because of my difficult subject matter, were excited that God, Jr. would be my ‘breakthrough’ novel when, of course, it wasn’t. I was already too stigmatised by my work’s reputation by then, so all God, Jr. did was confuse people who thought they understood me.

To return to The Sluts: When it was originally published, Facebook was still in its infancy and fake news as a term was not even on the horizon, which is to say that it has aged very well. The novel consists of online reviews and chats on gay message boards and dating sites. We don’t know who speaks and how many. There is no ‘truth’, just rumors and fantasy and they kind of spiral out of control. Since The Sluts predates social media and what I feel they have done to public discourse, I wonder a) to what extent (if at all) your outlook on the internet has changed since writing the novel and b) if anything about The Sluts feels outdated to you given that it takes place in a medium that has changed quite a bit on the surface?

Dennis Cooper: The premise and structure of The Sluts was based on a website that existed at the time where escorts advertised their services and clients posted their reviews and discourses about the escorts. There was a fair amount of fantasising and lying and fabricating going on there, not to the huge extent that takes place in The Sluts, but I was fascinated by the possibility that one could have created a massive ruse there a la The Sluts quite easily, and I just ripped the site off the internet and planted it on the inflexible paper of a novel and made that happen. I don’t know if you read my blog, but once a month I gather escort ads and client commentary/reviews from various existing escort sites and publish the most interesting ones with a bit of editing and disguising on my part, and although even now nothing as elaborate as what happens in The Sluts goes on on those sites, it gets close in some cases. So, in that sense, I guess The Sluts seems kind of prescient. I don’t think The Sluts has become dated — or not yet, although no doubt it will — mostly because the transfer of internet interactivity to the immobile printed page has a freezing in place effect, I think. I do think there might be a certain quaintness to The Sluts now given the current internet’s preponderance of wild conspiracy theorising and hacking attacks and click bait, etc., so maybe it has a vintage vibe in that sense, a kind of vinyl vs. mp3 effect or something.

I do check out your blog regularly and I’m amazed at how you manage to post something almost every day while also writing novels and making films. Do you have something like a workday schedule?

Dennis Cooper: Other the doing the p.s. section every morning, no. I just spend most of my free time making the blog posts. When I’m busy with another project or life-related stuff, I make myself find an hour or two every day to construct a post. When I’m inbetween things, as I am right now, as I’m mostly waiting for the funding to fall into place for Zac Farley’s and my new film and fiddling with some fiction ideas, I just direct the bulk of my creative energies into blog post making. I have tons of curiosity plus energy always, so I can be pretty productive. At the moment, I have blog posts built and lined up for launch for about three weeks in the future, which is about as far ahead as I ever get.

Your new novel I Wished returns to the muse of the George Miles circle. The novel is, I would argue, as much about your friend George as it is about you as an artist. My favorite section is the chapter “The Crater“. Here you write about the roden crater and James Turrell, who is molding it into an art installation. There is this funny line about Turrell, who you imagine thinking “I love and disrespect this old thing so much that I’ll devote my life to molding it into my greatest artwork”. That sentence reminds me of Joan Didion’s famous quote “writers are always selling somebody out”. Since you’re making it explicit in I Wished, did you ever have inhibitions about “molding” George Miles into art?

Dennis Cooper: When I was developing the Cycle, George was still alive. And I had many talks with him about what I was planning to do with those novels and how I intended to represent/misrepresent him. He was completely fine with what I was planning and was very encouraging. He was excited by the idea of being a malleable fictional vessel. As I’ve written about in I Wished, he felt very lost and unfocused as a person due to his disorder and the artificial effects that his medications imposed on him, and he was interested in the idea that could be crystalised into a cogent character. So I felt okay using him as a figurehead in the Cycle as I did. As you surely know, George killed himself before the first novel Closer was published, which I didn’t know until I was about to write the fifth and final novel Period. That very shocking news complicated the whole project for me very much, as I had thought he was somewhere reading the books. And that’s why Period is such a confused/confusing illusional kind of novel. I Wished was undertaken as a way to try to do George justice by representing him as he truly was as a person as best as I understood him. I think the novel is much more about me and what George does to my imagination than it is about him directly. I do feel very conflicted about turning George into art, and I think, or at least hope, that the novel makes that clear at every point.

I Wished is also a sort of plea that somebody who knew him might get in touch with you. He passed away a long time before the internet and you write you couldn’t track anybody down who knew him. Has the publication of I Wished lead to anything with regard to that?

Dennis Cooper: Soon after I Wished was published, a woman contacted me to say she read the novel and had used her resources as an employee of a newspaper to track down George’s brother. This was amazing to me because I had been trying off and on to locate his brother for many years. He’s a doctor, and she was able to find a phone number for his office, but not an email address. I’ve been debating ever since whether to call him, and I’m very hesitant to since I don’t know, first, if he knows about my books for George and what he would think about them, and, second, whether he would want talk about his brother since the end of George’s life and his suicide were very dramatic and traumatic for his family. So, I do have a way to contact George’s brother by phone, but I don’t know if I have the courage to approach him so directly. Other than that, no, no-one else who knew George has gotten in touch with me, at least not yet.

With I Wished, you once more stretch the common understanding of what a novel is as it rolls fairytale, memoir, essay and much more into one. It accomplishes the feat of being both structurally challenging while also being pretty easy to read and very relatable. The novel could also be read as both an end point and a new direction for you as a writer. Having turned to film in recent years, how much interest do you still have in the novel as an art form?

Dennis Cooper: I had a long standing plan to write 10 novels —the 5 Cycle novels and 5 post-cycle novels — and then stop writing them. I think I mostly liked the symmetry of 5/5, and I thought 10 novels is a lot from one writer. So I intended I Wished to be the last one, and when I became interested in making films and the gif fiction and put I Wished aside for about five years, I thought I would go back and finish it, and that would be that. But when I went back to it and finished it, and once I got back into that headspace, it was such a pleasure, and I felt the same excitement regarding the difficulty and challenges involved that I always had, so I decided I’m going to leave myself open to writing more novels if I feel like that’s the right form for what I want to do. So, yes, I seem to still be very interested in the novel. I’m just as excited about making films now, but I don’t see any reason why I can’t do both. We’ll see.

Recently, I think on the Apology podcast, you mentioned Joy Williams, who I also love. I’m perplexed as to how unknown she is! I think her new novel Harrow is absolutely incredible and she is probably my favorite short fiction writer ever. Final question: What’s your favorite Joy Williams book and why? And do you have an explanation for why she is this unknown entity?

Recently, I think on the Apology podcast, you mentioned Joy Williams, who I also love. I’m perplexed as to how unknown she is! I think her new novel Harrow is absolutely incredible and she is probably my favorite short fiction writer ever. Final question: What’s your favorite Joy Williams book and why? And do you have an explanation for why she is this unknown entity?

Dennis Cooper: Joy Williams is probably my favorite American writer. At least among living writers. I think John Ashbery is my all-time favorite American writer. It’s actually tough to choose one of her books as my favorite. I too really loved Harrow, and I think it’s way up there among her very best. Maybe The Quick and the Dead is my favorite of hers. That might be because it’s the first book of hers that I read, but, yeah, I guess that’s my pick if I have to choose one.

Beitragsbild: © Dennis Cooper